Published 4.26.2020

Plagues and natural disasters appear regularly throughout human history. No times, places, or people have been immune to these occurrences. During Japan’s Kamakura period a series of plagues and famines burned across the country. During the Kanki Famine in 1230-31 roughly a third of Japan’s population died—from 1.5 to 2 million people. In that year Dogen Zenji left the famine and sectarian strife of Kyoto to practice in an abandoned hermitage south of the city. I think of this as Dogen’s approach to social distancing in the 13thCentury.

What did Dogen rely on during this terrible time? Zazen for sure, but we don’t exactly know more, except, that in the midst of crisis he moved away from the center of the turmoil. Did he cultivate hope or radical hopelessness? Are they different? Dogen turned inward for a time, surely digging into zazen. He turned inward, then opening his dharma eye he widened the field of enlightened action and stepped forward into his world.

In 1231 Dogen began composing Shobogenzo, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, and wroteBendowa, the first expression of zazen in the Japanese language. Two years later he founded Kannondori Temple in Fukakusa, the locus of practice for his community over the next ten years, before he moved to Fukui Prefecture and built Eiheiji

The wayof our zazen practice is to turn inward, noticing and embracing everything that happens within us, which allows us to regulate and harmonize body and mind. Zazen enables us to put our mind in order. The purposeof our practice is, with a well-regulated mind, to take beings across to the shore of liberation. Theformof our sangha practice is to create an island of sanity in a world of turmoil. We do this by offering material needs, dharma teachings, and fearlessness. We reflect on justice, a sense of proper balance among all people and beings

In this pandemic moment we need all these offerings: inner reflection and work for justice. These are strange days. Streets are virtually empty but for people in masks, stores are shuttered, businesses are going broke, religious services have morphed into video conferences. We hardly dare to imagine the future. For the last month, as we practice social distancing to tamp down Covid-19’s impact, it is sometimes hard to know when we are turning inward and when we are moving in the wider world. Such provisional distinctions seem less clear with each passing day. It feels as if we are living in a dystopian novel, a bad dream. And we are writing that novel as we live it. But there is a lot of love out there. Warm greetings as strangers pass on the sidewalk.

At Berkeley Zen Center, where I live, we are sewing masks, offering food and funds to those in need, sweeping the temple grounds, and sustaining a daily zazen practice and Saturday dharma talks, cultivating fearlessness even as we learn of friends and family struck by the virus. Actually, we are sustaining Zen practice and it is sustaining us. Right now I am not much thinking about the future. There’s something fresh and creative about such “hopelessness.” Not to hope for things to return to some imagined normal, but to feel alive and full of questions right now, and now, and now.

We would never wish for a time like this, and we grieve for the thousands of lives lost from Coronavirus and from governmental irresponsibility. Still there is an opportunity here for each of us to stabilize our mind and be of service, as Dogen did in his own time of crisis. What is that opportunity for you? How does practice teach us to love each other?

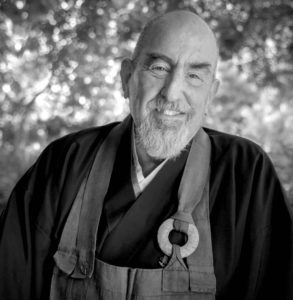

Hozan Alan Senauke is the Executive Director of the Clear View Project. He also oversees the Buddhist Humanitarian Project, an international initiative focused on responding to the Rohingya refugee crisis. Alan is Vice-Abbott of the Berkeley Zen Center and the former Executive Director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

As an author, Alan has written two books: Heirs To Ambedkar: The Rebirth of Engaged Buddhism in India and The Bodhisattva’s Embrace: Dispatches From Engaged Buddhism’s Front Lines. He was the co-editor of Safe Harbor: Ethics for Buddhist Communities. Alan’s numerous articles and essays can be found in the Clear View Project News & Essays section.

Clear View Project Clear View Project is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization based in Berkeley, California. A partner organization within the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, the Clear View Project has worked extensively on humanitarian projects throughout Myanmar, Bangladesh, and India.