The end begins on a sunny day at Shea Stadium, the Spring of 1972, the bosses secretary liked me, offered me two tickets or Saturday afternoon, a Mets game.

I loved the idea of taking my father, the opportunity to return a gift, symbolically, a token of appreciation for some of the most memorable times of my childhood.

So many times, my parents had taken me to a Dodgers’ game at Ebbets Field. Each trip was a pilgrimage. The Dodgers were our team, Daddy’s team, the team of Jackie Robinson, the team that had broken baseball’s color line, the most important symbolic blow for justice in my early life. The Dodgers were the working class team, the underdogs fated, it seemed until 1955, to finish second, to lose every year in the World Series to the upper class team, the hated Yankees, the lily-white Yankees.

At each game, I got a Dodger souvenir button with a picture on it of one of my heroes, — Jackie, Roy Campanella, Peewee Reese. I still remember all the names. Years later, at my first sesshin as the long days of sitting wound on, I tried to ward off the fatigue by recalling the Dodger line-up. And the Giant line-up, not quite hated but our rival every year for the pennant and the right of play the Yankees in the World Series. And the Yankee line-up. So many hours arguing whose guy was best. I defended Peewee against Alvin Dark and Phil Rizzuto, the Duke against Willie Mays and the Mick.

In those early days, the games were only on the radio. I still remembering crying when the Dodgers lost the World Series in the final game. Again.

That Day in May

But that day in May the sun was shining and I was grown-up and I had a good job and was taking Daddy to the game.

The Dodgers were long gone, the great betrayal of my childhood, abandoning me for sunny California where Aunt Lilly, daddy’s sister, and Uncle Alan lived.

I had loved the Dodgers and I had real New Yorker pride: we had three major league baseball teams, — no other city had more than two, — until the great betrayal when the Dodgers and the Giants fled. I gave up baseball. I couldn’t root for the Yankees. I didn’t embrace the Mets when they arrived, not until they made the miracle run to the World Series in 1969.

But here we were in 1972 on a sunny afternoon at Shea. Great seats. Jets overhead. Taking Daddy. Feeling like a success. There we were. In the stands. Was I eating a hotdog? Drinking a beer? People all around us. I have no idea what the score was. I have no idea what inning it was.

“I’m going to leave your mother. I’m moving out this week.”

I wanted to scream, I don’t know what. I wanted to but could say nothing, surrounded. I have no other memories of the day, how the game ended, how I got my father home, anything.

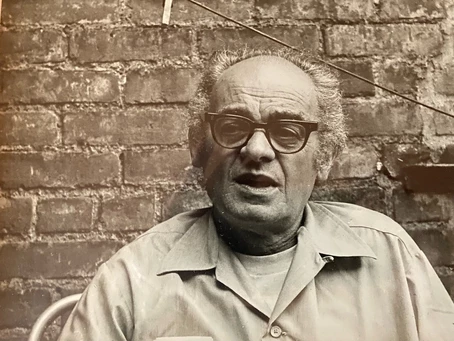

He moved into a basement apartment. I worried about him. He’d had a couple of heart attacks. For a while he had been traveling to Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx to ride a stationary bike in a coronary rehabilitation program. But after the last heart attack, lying in the bed in their second floor bedroom in the little house in Great Neck in which I had grown up from seventh grade until heading off to college, looking overall gray to me, telling me what a failure he had been. He didn’t explain but I knew what he meant. My mother had supported the family. He was a creative, a craftsman who made beautiful, custom furniture, painted all my life, oil on canvas, very much influenced by the Impressionists and to a lesser degree by Picasso who he admired very much and finally in later years sculpting in copper, wonderful sculptures, much less derivative, I thought, than his paintings. And he was an organizer. Totally dedicated to peace and freedom. Growing up, I often resented his dedication. He was out organizing so many evenings and on Sunday mornings when I wanted time with him, but I admired him. Always.

And yet there he was facing the end of his life, maybe for the first time, feeling like a failure.

Alone now in a basement apartment, who would take care of him? Find him if he had another heart attack? Call an ambulance? Joan and I visited him every weekend and then go to see my mother. She was having a very hard time. She was stunned. He hadn’t moved far away.

The Move

And then within weeks, it seemed, he told me he was moving in with Grace. I knew Grace. She and her husband and two kids lived around the corner from us. I like her husband, Saul. What had happened to him? She was a nurse. They had two kids. The older one, the daughter, a couple of years younger than me, had, I think, gone to the same summer camp I did for a couple of years. Grace was a nurse. That, at least, was a good thing. She would know what to do if Daddy had another heart attack.

But this, not surprisingly deepened my mother’s shame and grief and allowed her anger out. She was enraged that “they didn’t have the decency to leave Great Neck.” They were still there in town, part of the same circle of political friends, getting invited to the same dinner parties as my mother.

I felt my mother’s shame and anger. I had to agree with her. But I had to visit my father anyway.

He hadn’t left me. I had to go to Grace’s apartment, but I wouldn’t eat there. That much I owed my mother.

Birthdays

Then my father really wanted us to come for dinner on his birthday, December 8. Always an important date in my life because my birthday was December 7. I loved the coincidence. Joan and I went back and forth about it. I didn’t want to go but ended up deciding that I had to. Got through the evening. Somehow. Uncomfortable.

On December 9, I got a phone call. My father had suffered another heart attack. We visited him at North Shore Hospital on the tenth. He looked very gray. Like all the color had gone out of him. I don’t think he was awake while we were there. We went from the hospital to visit my mother.

She was upset. “I can’t believe you spent your birthday with your father and that woman.”

I tried to explain, “It was his birthday.”

I don’t think she was satisfied.

Early in the morning on December 12, maybe 2 AM, I got a call from the hospital. My father had died.

I didn’t think they were supposed to break the news this way, over the phone, totally without sympathy. I thought they were supposed to tell me that my father had taken a turn for the worse, that I better get there quickly. We could have jumped in the car and rushed to Great Neck. Then, I thought, they were supposed to tell me while I was sitting down, “We’re so sorry. We did everything that we could.” Blah, blah, blah. Et cetera. Etcetera.

I never saw my father again. He had willed his body to Downstate Medical Center. I had known about that but I hadn’t realized that they would collect him so quickly. He had gone off to train the next generation of doctors.

Joan and I stayed at my mother’s that week for a non-religious Shiva. The house was constantly full of people. And we planned a memorial service. Someone arranged for it to be held at the Universalist Church. My parents were not members (although my mother later joined) but my father had worked with them. They all supported peace and justice.

The Most Moving

Somehow I asserted myself. I did not want all the eulogies to be just about Daddy’s political activity. My daddy was more than a political organizer. I insisted that Bobby Moss speak. Bobby and my father had both served in World War II. Both left young wives at home. And with sons named Kenneth. My mother and Lucille found themselves living across the hall from each other in the Queensboro Federal Housing Project, one of the first federal housing complexes in New York City. Mostly all women and young children. The men were all away at war.

My father and Bobby came home around the same time. My father came back in one piece. Bobby was not so lucky, came back a paraplegic. I don’t think anyone expected Bobby to outlive my father, although he was much younger. They were friends although they had their differences. My father was not willing to ignore political differences with many people. He respected the important role which Bobby had played in organizing paralyzed veterans and the rights which he had helped to win. I knew that Bobby would present a fuller picture than the other speakers. He did.

And there was a card from my father’s students at the Long Island BOCES where he had been teaching in the last year of his life. Having given up his cabinet shop, he had become a woodworking teacher. I think in that last year he was very proud of this. He had admired my mother’s career as a teacher more than I had realized. Even envied her. Applying for the job, he had discovered that not only hadn’t he graduated from college, — he had run away to sea during his freshman year at Dalhousie, –he hadn’t graduated from high school either. Only then had he realized that, having left high school early to enter college, his high school graduation had been contingent on his completing his freshman year. In order to teach at BOCES, he had to take the High School Equivalency exam.

Bobby’s eulogy and the notes from Daddy’s students were the two most moving parts of the memorial. At least for me. My mother was the principal mourner. I do not remember if Grace was there, a forgotten aberration in an otherwise exemplary life.

An Obligation

Joan and I stayed around now that the house was empty. During the days of Shiva I had begun to realize how fortunate I was that we had decided to do the birthday dinner, how I could never have digested it had I hung onto my anger as the conclusion of my life with my father.

At some point during those days, I went over to visit Grace, an obligation I felt. My father would have wanted me to remain connected. I dragged Joan along. My father had moved in with his most prized books and much of his copper sculptures. I was very uncomfortable.

Her daughter talked to me about much she and I had lost.

You have to be kidding,” I thought. “My father was barely in your life a couple of months.” I felt nothing in common.

Grace offered me one piece of my father’s sculpture. She made clear that all the rest belonged to her. I was shocked, hurt. She was grabbing my legacy.

Joan and I didn’t stay long. We didn’t eat anything. As we left her apartment building, I felt an immediate sense of relief. Grace had relieved me of my obligation to her. I never saw her again. My father understood.

It freed my mother too. There was no need for her to share me with the other woman.

That afternoon, a big, old, white Tom cat was sitting upright in the middle of my mother’s backyard. He stayed for two days. Just sitting there. We had never seen that cat before. And then he was gone. We never saw that cat again.

I am not at all a believer in the paranormal, but that cat was certainly Daddy, paying his final respects to my mother.

Joan agreed. She was a believer in cats.

After that Joan and I went back to the city and our workaday world. And my mother settled into widowhood, the aberration of the final year forgotten, or nearly so. That spring she travelled to Mongolia and slept in a yurt.

Two weeks after the memorial, my father’s High School Equivalency Diploma arrived in my mother’s mail.