Peace offerings of tobacco ties adorn the fence at the Wounded Knee Memorial on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota on Oct. 20, 2014. (Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post)

With the flashlight from her smartphone, Renee Iron Hawk peered into the dust-covered glass and wood cabinets inside a small, dark museum in Barre, Mass.

She and a handful of other American Indians looked at pairs of beaded moccasins, a dozen ceremonial pipes, and a few cradleboards, used by women to carry infants on their backs. The items are among as many as 200 artifacts that were stolen from the bodies of the 250 Lakota men, women and children slaughtered by the U.S. Army in 1890 during the Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota. They’d ended up in an obscure museum attached to a public library in a rural town 70 miles from Boston.

“Going through those cabinets, looking at these items of our people with the light from our phones, it was just something deep to me,” Iron Hawk said. “It felt like the breath went out of me. I had to sit down and rest. I had to say a prayer.”

How a collection from one of history’s worst atrocities against American Indians ended up in Barre is almost as painful as the memory of the massacre.

Some of the items were sold by gravediggers to Frank Root, a traveling shoe salesman from Barre, who used them as part of his Wild West roadshow before he donated them in 1892 to the town’s museum, where they’ve stayed for more than a century. They are among the more than 780,000 burial items and possessions of Native Americans held in museums or other institutions as of September 2021, according to a report to Congress.

“It’s a stolen collection,” Iron Hawk said of the Barre objects. “Just like they stole our lands; it’s the same.”

Manny Iron Hawk of the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota shows a photo of his grandmother Alice Ghost Horse, who survived the Wounded Knee massacre in 1890, during a town hall meeting in Barre, Mass., on April 6, 2022. (Christine Peterson/Telegram & Gazette)

Now she, her husband, Manny, and their group, HAWK 1890 — which stands for Heartbeat at Wounded Knee and includes American Indians whose relatives were slain in or survived the massacre — have launched an effort to have the items returned to their tribes, the Oglala Lakota and Cheyenne River Sioux.

This tribe helped the Pilgrims survive for their first Thanksgiving. They still regret it 400 years later.

Earlier this year, they seemed to be on the verge of a breakthrough. But the deal they struck this spring with officials from the Barre Museum Association has stalled, leaving the Indians fearing a repeat of the country’s long history of broken promises to Native Americans.

Museum officials insist that is not the case but also say they must follow protocols to ensure that the objects are returned properly.

The delays have frustrated the Indians. Without those items in their tribal homelands, Manny Iron Hawk said, they believe their ancestors are in limbo.

“For our way of life, when somebody makes their journey to the other side, their spirit has to go and be released,” said Manny, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River tribe and a great-great-grandson of a man killed at Wounded Knee. “That didn’t happen for these ancestors.”

He said their items and objects need to be brought back “so we can do the proper ceremony and their spirits can take that journey to the other side. They need to come home.”

‘A straight-up massacre’

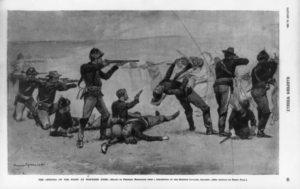

An 1891 illustration, from Harper’s Weekly, by Frederic Remington showing the opening of the fight at Wounded Knee with the Seventh Cavalry in battle with Indians at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. (Library of Congress)

An 1891 illustration, from Harper’s Weekly, by Frederic Remington showing the opening of the fight at Wounded Knee with the Seventh Cavalry in battle with Indians at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. (Library of Congress)

American Indians were struggling to survive in the years leading up to Wounded Knee. The huge herds of buffalo on which they depended were gone. They had been forced off their lands and onto reservations. They had suffered devastating losses in battle and betrayals when the United States broke treaties it had signed with them.

A census record from 1890 showed “Indians were vanishing,” according to Jim Adams, a senior historian with the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington.

This was the worst slaughter of Native Americans in U.S. history. Few remember it.

Their suffering fueled a revival of the “Ghost Dance,” a spiritual movement embraced by some American Indians who believed it would make the White men disappear, resurrect dead Indians and bring back the buffalo herds.

In 1890, the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment was sent with the largest deployment of federal troops since the end of the Civil War to stop the rise of the Ghost Dance. Soldiers tried to arrest Sitting Bull, one of the most renowned Lakota chiefs. Instead, an altercation broke out, and Sitting Bull was shot and killed at the Standing Rock reservation.