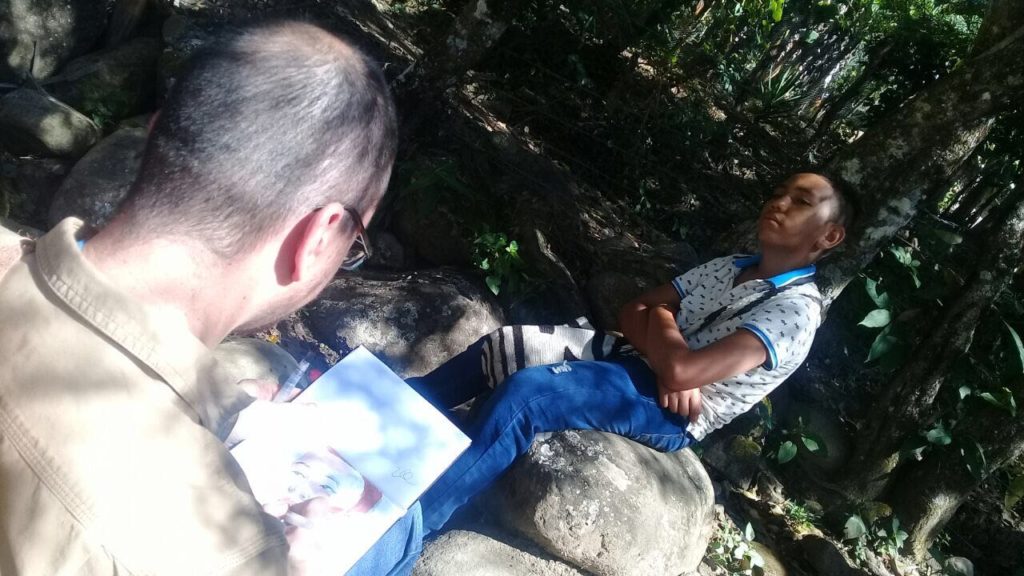

Above photo by Angelica M. Cuevas, Dejusticia. All other photos by ZPI staff unless otherwise noted.

Anthony: This is Thursday December the 21, 2017. I’m at the Zen Peacemakers office in Montague MA with Executive Director Rami Efal, who has just returned from Colombia. You participated in an indigenous leaders workshop there.

Rami: Yes. We all met in Bogotá, Colombia. That’s where the headquarters of Dejusticia is which is a nonprofit co-founded and directed by César Rodríguez Garavito, a ZPI member. They’re an international human rights advocacy group– they run trainings and immersion programs all over the world, as well as conduct litigation for human rights causes and were involved in the recent peace-process in Colombia. In fact César was invited to attend a meeting with the pope on the second day of our workshop for a climate day summit. So he had to leave, got on a plane to Italy, meet the pope, and come back. César came with the Zen Peacemakers to Auschwitz in 2016, then again to the Week of Service in Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Reservation in 2017, and I enjoyed connecting with him and finding we have so much in common, as do the organizations we represent.

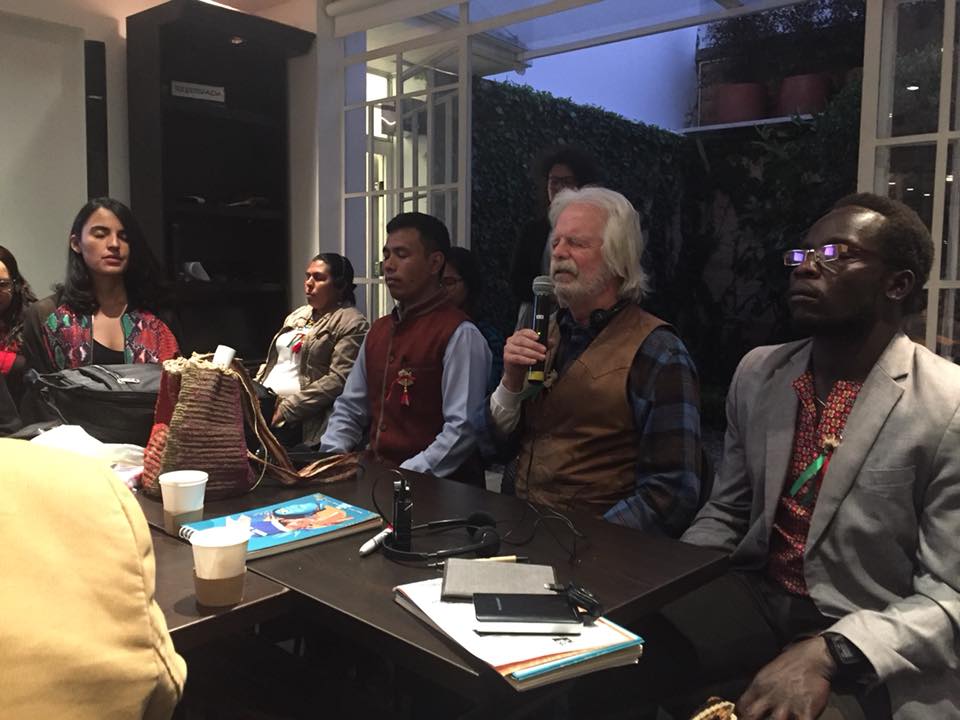

So this program started in Bogotá at their Headquarters, where we met Dejusticia’s staff and the program leader Carlos Andrés Baquero. We were coming together– it was just thirty people in a small room and each person there was indigenous from their own communities. Genro Gauntt, Paco Lugovina, Noemi Santana and myself came from Zen Peacemakers– Tiokasin Ghosthorse, who led us in the Bearing Witness retreat in 2015 and the plunge in 2016 in South Dakota, came as a presenter.

Joining together were indigenous leaders from all over the globe. There was Shirley Kimmayong, an Ifugao indigenous woman from the northern mountains of the Philippines. There were Sreyneang Loek and Neth Prak, a Bunong woman and man from Cambodia. From Africa there was Elhadji Samba ‘Ardo’ Sow, he was Senegalese; Evariste Ndikumana, a Batwa who came from Burundi (Batwa are an indigenous group that was affected by the 1994 genocide in Rwanda); Benson Khemis Soro Lako from South Sudan; Karimu Unusa from Cameroon. There was Liaquat Ali, a Hazara man– Hazara are an indigenous group that spans Pakistan and Afghanistan and whose main city, Quetta in Afghanistan, is a recurring target for large scale terrorist attacks. Ruth Anna Buffalo came from North Dakota, close to Standing Rock. There were several participants from Amazon communities: Asunción Jiménez from Oaxaca Mexico and Sofía Fuentes from Ecuador…There were more and I’ll mention them further on.

(Editors note: A Native American from Eagle Butte, South Dakota USA and a woman from Pakistan couldn’t come because of immigration issues, their story was told in this Dejusticia blog post.)

Anthony: Thirty people total?

R: Yes. This was called the First Workshop for Indigenous Leaders. The purpose of the meeting was to educate indigenous leaders in common strategies for facing governments, wherever they are.

On the second morning, everybody got on buses and got on a plane and flew to Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, which is the territory of the indigenous Kankuamo, Kogi, Arhuaco and Wiwa. The workshop components – education and strategizing– happened while in a full-immersion in three different villages of the Kankuamo: Atánquez, Chemesquemena & Guatapurí.

Each community was different in resources, means, and access. We were staying at people’s homes in any given village we visited. You’d see a chicken here- donkey there- and we’d be waking up with the roosters. And then the next village was a bit more affluent. You could see it by the roaming dogs, they had more flesh on them. One local person at the village referred to another local as an ‘indigenous.’ I assumed that even though both were officially Kankuamo, some are considered internally as– for the lack of a better word –’more indigenous,’ maybe based on their even more simplified lifestyle and less dependance on modern means.

A: So you flew from Bogota into Valledupar which is developed enough that there was a place to land a plane. How’d you get between the communities after that?

R: Some of the car rides were very long and that’s when much of the bonding took place. On one of them, I talked to Kriz Perez, a Filipino staff member of Dejusticia, about the Zen Peacemakers and Bearing Witness, and she said “we have a word for bearing witness in Filipino — Pakikipamuhay, literally meaning ‘the act of living with.'”

Dejusticia staff, much to the efforts of Carlos Andrés Baquero, developed a whole program along with the leaders in these communities. The communities provided home-stays, meals and drivers with 4x4s that drove us everywhere. The communities also provided food, did the community and cultural events organizing, and invited the elders that were with us the whole time. So the whole task of hosting was really in the hands of the local community, with collaboration and support from Dejusticia.

A: How big were these communities? Did they vary much in size?

R: Census data puts the total number of Kankuamo at 23,042, and that includes the four groups. We were just in one area.

TRAININGS IN SOLIDARITY AND ACTION

R: In addition to the locals and global indigenous leaders, there were also presenters and scholars who came. James Anaya, he’s a professor of law at Colorado University and Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. If people wanted to petition to the UN about rights violations of indigenous people, they’d go to James, that was his role. He’d heard so many stories from all over the world so he came with all this knowledge. He spoke to us about the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples including the clause of Free, prior and informed consent, which most governments don’t apply.

We learned about the ‘black line’ of the Kankuamo, the sacred perimeter that defines their territory, but is not recognized by the government. The basic thing many indigenous communities experience, in the best cases, is having a government agent come to them saying, “Hey, tomorrow we’re gonna be drilling in your backyard”, and in the worst case they just have the drillers come. So the whole idea of coming and asking the community, “Do you consent to this?”– that’s one thing. But then consultation is a whole other thing. Why is the only conversation around consent? As if anyone would give consent to have their rights violated. Maybe the locals don’t want that. Maybe the locals have a whole other framework.

As a side note, I had a personal insight about how I heard the word ‘consent’ used in this context of indigenous peoples– it’s so similar to how I hear it in the context of women’s rights and sexual harassment. It highlighted to me how in both cases greed is present, and the act of taking without permission.

Back to the workshop, the ideas of consent and consultation brought up a whole other conversation: how the Western sense of democracy may include an inherent flaw, that “my vote is equal to your vote is equal to an indigenous person’s vote, because we’re all equal.” That doesn’t address two sensitivities. One: there are groups that may have specific needs and rights– think Black Lives Matters, Muslims, or LGBTQ –and some of us feel called to address them differently, perhaps because they were subject to slavery or genocide or are now subject to discrimination. These groups will simply never get a democratic majority. Democratic process doesn’t inherently address this.

And the second thing is that the indigenous leaders say “Why are we only giving votes to people? I consult with the forest and with the birds, with the snow and with the wind. Their territory is their body, that’s what they say– “The territory is my body.” They speak– it’s much like Bernie –they say “My body is the trees, you cut down the trees, I feel it.” Why aren’t these given a vote, a voice? Where is that in the democratic process when we make decisions? Obviously modern democratic models don’t address that.

Some of the presentations were from indigenous people who, based in their tribes and territories, cut their hair, put on a suit and learned to talk the ‘legal lingo,’ learned how to develop strategies, and enter the big cities and capitals of politics and economics. One said, “You know we were so simple, we were village dwellers and we didn’t know the language– first we needed to organize.” Patricia Tobón Yagarí is an Emberá indigenous attorney who currently works with the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia. She said that her elders designated her at age ten to be the first college-educated lawyer-leader to come out and deal and respond to her people’s needs. For twenty years she was groomed by her village to do that.

Whenever she came to meetings, everyone expected an elderly woman in the traditional cultural dress– but no, she had her suit and her smarts. And another woman, Patricia Gualinga, a Kichwa-Sarayaku leader from the Ecuadorian Amazon, gave two riveting presentations about the many legal battles she fought in Ecuador and in international courts, how she had never lost one of them. (Editors note: watch a video of about the Sarayaku in Equador, featuring Patricia Gaulinga.)

A: The idea about consulting with the local forest, the birds is really interesting. I’m drawing a parallel between empathy toward the non-human inhabitants of a community and including a sense of wisdom in democracy…In contemporary politics “wisdom” is a piece of vocabulary that is totally absent.

R: Yes, the lawyers with us talked about how challenging it is to explain the cycles of ecosystem before the courts. When protecting water, it’s not just about water. To explain the whole process of ecosystems, both physically and spiritually, is one of these things that’s very challenging to explain.

CEREMONY & CREATIVITY

R: Every morning and every evening the group was led in “spiritual harmonization” by the Mamos, who are the spiritual leaders of the Kankuamo.

The Mamos invited us to do a ceremony with them, inside their gathering huts called Kankurwas. There was one hut for men and one for women, and each one represents one of the two nearby mountains of the Sierra Nevadas– one’s called the father and one’s called the Mother. So when you go into the hut, you walk into the mountain, into their mother and father. The Mamos led a sharing circle, like council, asking to hear from us, the guests.

They told us that just recently someone torched the Kankurwas, the sacred huts in a nearby village. And then they said, “We can either spend time finding who did it, or we can spend time constructing new Kankurwas– because until we have the next place of worship we won’t be able to forgive. So we must build it first, then find the person who torched it.”

The Mamos every morning would give us a little piece of cotton and told us they were recorders. They’ll record all your thoughts and feelings. And at the end of the day we had to give it back to the medicine man.

We led council groups with people from North Dakota, from South Sudan…you’d hear all these stories. Many spoke about displacement, about challenges with religious, women’s and indigenous rights, about keeping tradition, language– language was a big subject.

It was beautiful to see the connections between the Colombians and the Africans because they’re both very gregarious people, they love music and dancing. And it was also interesting that there are 3rd or 4th or 5th generation Carribean ‘Afro-Colombians,’ sometimes referred to as ‘Afros,’ who are descendants of enslaved people from Africa. It was moving to listen to poems written and read by one of our participants, a man from Senegal, about how he related to the ‘Afros,’ the connection he felt. Senegal used to be one of the western African states from which enslaved Africans would be shipped to the Caribbean.

Laura Salas, an organizer and filmmaker from the human rights advocacy organization Witness, which was founded by the musician Peter Gabriel, brought a methodology to create a documentary in 48 hours. It activated the group. It wasn’t a film crew that came in to film but the participants themselves were conducting the interviews, shooting the videos, recording the audio, and then bringing everything together. In three days we did a ten-minute documentary. It was amazing and it developed bonds between us because we had to work together, working with cultural differences and language barriers. All the community gathered in the school one night to watch the premier, and the Dejusticia staff led us in a community process of choosing the title.

As well as the documentary, Mario Murillo, a Colombian-New Yorker radio creator, led the group in creating a radio podcast. In both these creative projects we drew on people’s skills and talents – some were radio professionals, like Diana Jembuel from Colombia and Devkumar Sunuwar from Nepal, others were film professionals like Ronald Suárez from the Peruvian Amazon and Fredrick Ssenyonga from Uganda. I can draw, so I painted portraits of the individuals we interviewed and used them in the film. The place was buzzing with creativity and energy.

Zen Peacemakers Genro Gauntt, Noemi Santana, Paco Lugovina and myself were invited to share about ZPI and lead council and meditation at different times during the week. The whole program aligned very well with our ongoing Native American Bearing Witness and Service programs. I thought the workshop was a real celebration of diversity and global indigenous solidarity, and a wonderful result and expression of the Three Tenets, constantly exploring and adapting, with ample opportunity to take actions and plant seeds for new ones. I am inspired by César’s and Dejusticia’s work. It had profound effect on individuals through whom change will continue to ripple.

—

Learn more about the Kankuamo in this video

About Rami Efal. A dual citizen of Israel and the USA, Rami has been a student of Zen Buddhism since 2005 and has lived for 4 years at Zen Mountain Monastery and Zen Center of New York City. He met Bernie Glassman at the 2013 Auschwitz Retreat, became his attendant in 2015 and, following Bernie’s stroke in 2016, was hired as the executive director of Zen Peacemakers International. Since then Rami has organized all aspects of the organization, including the Auschwitz and Native American Bearing Witness programs. Prior to this, Rami participated in Israeli-Palestinian dialogues in New York City, trained in peace-building at Vermont’s School of International Training, co-led multi-day workshops in Nonviolent Communication with the New York Center for NVC, and was an illustrator and fine artist. He presented on art and peace-building at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, on NPR and at the UN headquarters in New York City.

About Rami Efal. A dual citizen of Israel and the USA, Rami has been a student of Zen Buddhism since 2005 and has lived for 4 years at Zen Mountain Monastery and Zen Center of New York City. He met Bernie Glassman at the 2013 Auschwitz Retreat, became his attendant in 2015 and, following Bernie’s stroke in 2016, was hired as the executive director of Zen Peacemakers International. Since then Rami has organized all aspects of the organization, including the Auschwitz and Native American Bearing Witness programs. Prior to this, Rami participated in Israeli-Palestinian dialogues in New York City, trained in peace-building at Vermont’s School of International Training, co-led multi-day workshops in Nonviolent Communication with the New York Center for NVC, and was an illustrator and fine artist. He presented on art and peace-building at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, on NPR and at the UN headquarters in New York City.