“The opposite of poverty is not wealth — it’s justice,”

– Bryan Stevenson

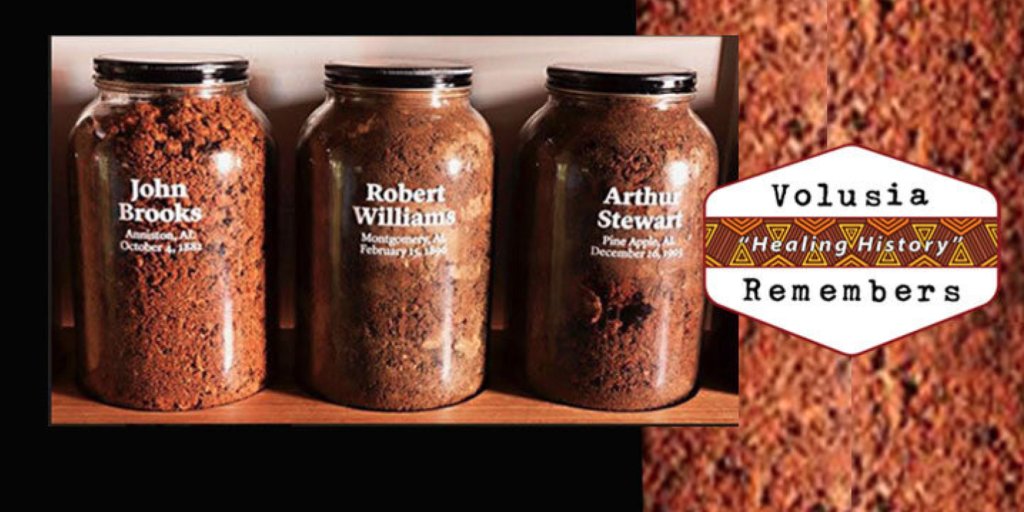

Volusia Remembers is a diverse local organization of volunteers committed to healing divisions within the community through acknowledging, understanding and confronting painful events in Volusia County’s history. Volusia Remembers’ mission is to remember, acknowledge, and reflect upon our history of racial terror by partnering with the Equal Justice Initiative to install monuments to victims of lynching in Volusia County.

Volusia Remembers’ goals are to:

- HONOR – Remember lynching victims and celebrate civil rights victories.

- EDUCATE – Explore our divided past and chart a united future.

- RECONCILE – Cultivate healing and reconciliation.

In April of 2020, Volusia Remembers officially became a Community Partner of EJI, the Equal Justice Initiative. Through this partnership, Volusia Remembers:

- Will gather soil for remembrance at the sites of documented lynchings in Volusia County·

- Will erect historical markers at the lynching sites

- Will install in Volusia County a replica of the Volusia monument now displayed at theNational Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL

The Victims

The lynching of African Americans was a widely supported campaign to enforce racial subordination and segregation during the period between Reconstruction and World War II. ”Lynching in America,” a report by the Equal Justice Initiative, documents more than 6,000 racial terror lynchings in the United States during this period. These events did not occur solely “somewhere else.” The EJI has identified and documented five cases of lynching in Volusia County, Florida. Additional research has been undertaken by The Volusia Remembers Coalition using original sources, including newspaper articles and public letters from the time of the event. As additional research yields more details, we will update this list.

Lee Bailey | September 26, 1891

Lee Bailey had recently been employed by J.R. Wetherell in DeLand. While Mr. Wetherell was out of town, attending to business, Mrs. Wetherell, alone in their house on south Amelia, reported to a neighbor that she had been raped. Mr. Bailey was soon arrested and identified by Mrs. Wetherell. As the local paper, The Florida Agriculturist Supplement, reported at the time. Mr. Bailey had the “same straight hair, the peculiar shaped head, the woolen shirt and his breath was impregnated with whiskey. The negro who committed the dastardly deed had all of these” (September 30, 1891). On this basis, an “indignant” white mob overwhelmed the sheriff at the jail that night and dragged Mr. Bailey to a nearby oak on Rich Avenue, not far from the jail, where he was hanged and his body riddled by bullets. The Agriculturist proclaimed in its headline that this was “A JUST FATE!” Charges of sexual assault by Black men against White women were often enough to justify White lynchmobs. Upholding the “purity” of White Southern womanhood and presenting Black men as over-sexualized and violent reinforced a key idea underpinning Jim Crow segregation and anti-Black racism.

Anthony Johnson | September 17, 1896

Anthony Johnson, an agricultural worker, was lynched with Charles Harris in or near DeLand. The exact location and other circumstances are currently unknown. We know only that Mr. Johnson and Mr. Harris were not given a chance to defend themselves in court against an allegation that they had assaulted an eight-year-old

White girl, Eva Bruce. Racial terror lynchings, where the alleged victim was a White woman or girl, were common place during the Jim Crow era. The Equal Justice Initiative has now documented well over 6000 racial terror incidents; a good number of these cases fall into this pattern. White lynchers were almost never brought to justice for their racial terror murders. Victims never had an opportunity to defend themselves.

Charles Harris | September 17, 1896

Charles Harris was also an agricultural worker. We don’t know much else about his life, other than that he was lynched alongside Anthony Johnson in or near DeLand. Both Mr. Harris and Mr. Johnson were accused of assaulting an eight-year-old White girl, Eva Bruce. That charge was never tested in court, because the two men were lynched by a White mob before they had a chance to defend themselves. In the Jim Crow era, a complaint about a criminal assault of a White woman or girl was commonly given as a justification for lynching.Protecting the “purity” of White women was part of the ideology to keep Blacks separate and lower than Whites. Whites, even though well-known in the community and sometimes even when they were pictured in local newspapers, were almost never prosecuted for lynching Black men.

Herbert Brooks | July 31, 1920

Herbert Brooks, a twenty-four-year-old British subject from Nassau in the Bahamas, was living in Miami, when he was arrested in a door-to-door search of Black residences because, deputies alleged, his description fit “in a general way” the description given by a fifty-five-year-old White woman who reported being assaulted nearby. A White mob of some 1200 men surrounded the city jail. For safe keeping, Sheriff D.W. Moran decided to transport Mr. Brooks out of town by train, ultimately to a jail in Jacksonville. Returning to Miami for trial, Mr. Brooks was alleged to have jumped from the train, dying after his head struck the tracks just north of Daytona Beach. He was accompanied by deputies and shackled and handcuffed at the time. An autopsy was performed in Daytona Beach and another, at the request of the British Consulate in Miami. After reviewing the autopsy results and description of injuries, which did not indicate any head injuries, some Bahamians and Blacks inMiami concluded that Brooks was beaten to death before being brought onto the train and then dumped on the tracks. This story—a Black man murdered in police custody after an arrest for an alleged crime against a Whitewoman—is often repeated during this period. Mr. Brooks never had an opportunity to defend himself in court.

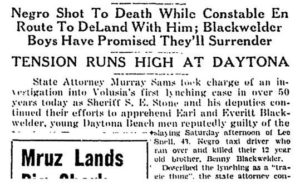

Lee Snell | April 29, 1939

Lee Snell, a resident of Daytona Beach, was a veteran of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, a branch of service open to African Americans in the strictly segregated military of that time. After his service, he returned home to a hero’s welcome; his military service is memorialized today on a plaque at Halifax Hospital. Mr. Snell became a respected member of the community and a successful entrepreneur, owning his own taxi service in Daytona Beach.

In 1939, in an early morning accident, a White child on a bicycle, Benny Blackwelder, collided with Mr. Snell’s taxi. It is unclear whether Mr. Snell’s taxi struck the boy, or the boy collided with the taxi. The boy was rushed to Halifax Hospital where, sadly, he died. Mr. Snell, shaken, submitted to arrest at the scene, and was taken to the Daytona jail on the charge of manslaughter. When a White mob was rumored to be forming, inflamed by the boy’s older brothers, Everett and Earl Blackwelder, the decision was made, and widely announced, that a single White constable, James Durden, would escort Mr. Snell by car to the County Jail in DeLand for safe-keeping. Before Mr. Snell could defend himself through the legal process, however, he was lynched by the older Blackwelders, by the side of the old brick highway between Daytona and DeLand.

Drawing on eyewitness testimony and newspaper accounts at the time, historian Walter T. Howard offers this chilling description of the lynching, allowing us to feel the moments of terror Mr. Snell must have experienced. The Blackwelders forced the constable’s car to the side of the brick road and dragged Mr. Snell from the car, beating him with the stocks of their rifle and shotgun. As Mr. Snell was “clinging tightly for his life to the officer’s arm,” Earl shot him with his high-powered rifle. “The injured man fled in panic,” Howard writes. “Everett shot him in the left knee, and as he fell, Earl shot him twice in the upper body” (Lynchings: Extralegal Violence in Florida during the 1930s, 124-132).

There was a trial, but Constable Durden and other witnesses refused to identify the Blackwelders in court as his murderers, and so they were released.

The lynching of Lee Snell attracted state and national attention. Volusia County educator and legendary civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune, at the time, wrote a letter to the editors of Florida’s newspapers to ask for justice for Mr. Snell. “The eyes of America and the world,” she wrote, “are turned this way taking note of your standard of justice.” Some small measure of justice was restored in 2020 when members of the VolusiaRemembers Coalition gathered to honor Mr. Snell on Memorial Day and to lay a wreath on his marble military tombstone in Daytona Beach. Our first soil collection, is scheduled for February 27, 2021 (during ZPI’s Race In America: An Intimate Plunge). The soil collection will be at the site of Lee Snell’s lynching on the Old DeLand Highway.

Healing hard history: Remembering the first of five black Volusians lynched

BY EVAN KELLER Volusia Remembers Communications Chair | May 29, 2020 | Published in The West Volusia Beacon

Memorial Day weekend is a fitting setting to remember Lee Snell, a World War I Army veteran, who, in 1939, was the victim of racial terror by lynching in Daytona Beach.

Pfc. Snell is the first of the Volusia Five to be memorialized in the Volusia Remembers initiative, through a Saturday-morning service at his little-known grave in the Mount Ararat Cemetery in Daytona Beach.

In attendance were veterans, dignitaries, university historians, and local NAACP chapter leaders.

Intentionally a small gathering (with social distancing practiced) due to the current pandemic, participants stood in a wide circle and took turns sharing with each other — and with a broader audience via Facebook Live — what is known about this honorable man, who was denied all honor when his blood was spilled in extralegal violence.

The historical setting of Snell’s death was the Jim Crow era, in which the largely unpunished practice of lynching claimed more than 5,000 black victims, Bethune-Cookman University history professor Rick Buckelew said during the service. Those involved terrorized the remaining black population into submission to laws and norms meant to subjugate them as subhuman.

Mary Allen, director of DeLand’s African American Museum of the Arts, eulogized a man who should have remained alive into her own lifetime. Unfortunately, Mr. Snell’s life was snuffed out with a firearm on April 29, 1939, in a highway ambush involving a deputy’s vehicle, in which Snell was supposedly under protective custody.

As was common in the era of lynching, the extralegal execution was carried out with brash impunity, inflicting Snell’s family with a grief devoid of justice.

Allen pointed out that in 43 short years, Mr.Snell had accomplished much, especially inthe context of the extremely limited opportunities afforded to black men in the Jim Crow South.

In addition to serving his country in the trenches in France, he was a family man, he owned his own taxicab, and he was held in high esteem by the local black community.

His high standing in the community was evidenced by the large crowd of supporters attending a hearing regarding the accidental death of a young white male bicyclist who strayed into traffic and was struck by Mr.Snell’s taxicab.

No one at the inquest accused Mr. Snell of driving carelessly, much less of striking the youth intentionally.

Fast-forwarding to the present, and, sadly, none of Snell’s living relatives were able to attend Saturday’s memorial to share stories of his life to reveal more of his true character.

As Rina Arroyo of Stetson Universityshared beside Mr. Snell’s gravestone, ourpartners at the Equal Justice Initiative hope “a new era of truth-telling” will catalyze a “beloved community” here in Volusia County and around the country.

“I am not interested in punishing America with this history. I want to liberate us,” Equal Justice Initiative founder Bryan Stevenson said. “I think we are a nation that has never truly sought truth and reconciliation. We are not going to be free, really free, until we pursue that.”

This sentiment was echoed by retired Judge Hubert Grimesat the Mount Ararat Cemetery.

“White Americans have never apologized for slavery; thus black Americans have never forgiven them for it,” he said.

By confronting this hard history, Volusia Remembers seeks to heal our festering racial wounds and forge a reconciled and united future.

At Saturday’s memorial, Daytona Beach Mayor Derrick Henry spoke up to honor Mr. Snell, affirm the work of the coalition, and offer his unreserved support of Volusia Remembers.

He noted that some have considered Daytona Beach to be “above the curve” due to the extraordinary achievements of black educator Mary McLeod Bethune, but cautioned against accepting that superficial reading of our history.

Volusia Remembers is striving to embody this healing and team work across the color line, which we hope will become as common as the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Cessna planes that made it hard to hear the morning’s presenters.

Those deadened voices remind us that the sorrow-laden voices of Lee Snell’s people have been suppressed for 400 years.

While airplane engines drowned out some of the words of remembrance, songbirds seemed to accentuate them – hinting at the joyful melody of the “beloved community” that Volusia Remembers hopes to nurture.

After a prayer offered by the Rev. Reginald Williams, the memorial ended with a song of human voices – “God Bless America” – emphasizing the grace we’ll need to receive and share with each other in order to forge a future of trust and joyful friendship.

Belated by 81 years, Black and White Volusians jointly decorated Mr. Snell’s grave with a U.S. flag, a patriotic wreath, and even a ceremonial libation (a traditional way to honor ancestors) around a freshly cleaned tombstone.

With various upcoming events, including the collection and display of soil from lynching sites and the installation of historical markers and monuments, the Volusia Remembers Coalition will continue to use history to shed light on present-day racial tensions and start a hopeful dialogue leading toward a positive future — together.

volusiaremembers.org | info@volusiaremembers.org | facebook.com/volusiaremembers