The article that follows was a blog post originally written by ZPI founder Bernie Glassman on October 5th, 2013, right before the Zen Peacemaker’s 19th global, multi-faith Bearing Witness retreat at Auschwitz. Here he shares his reflections about his returning to Auschwitz-Birkenau year-after-year, and the purpose it has served for both him and others within the community of peacemakers.

BERNIE: This year I’m returning again to Auschwitz-Birkenau. I go almost every year. People wonder why I go back there. They weren’t surprised the first time I traveled to Poland, in 1994, to visit the biggest of the death camps. I’ve been a Zen Buddhist priest and a teacher of Zen for many years, and I’m also a Jew from Brooklyn whose mother originally came from Poland. In November 2013, the Zen Peacemakers will be conducting its 19th global, multi-faith Bearing Witness retreat at Auschwitz, and I will be there once again. Strictly speaking, my presence isn’t necessary at the retreat. A number of leaders and teachers from different religious traditions will be there. So why do I return? Why does a Zen teacher go back to Auschwitz-Birkenau again and again?

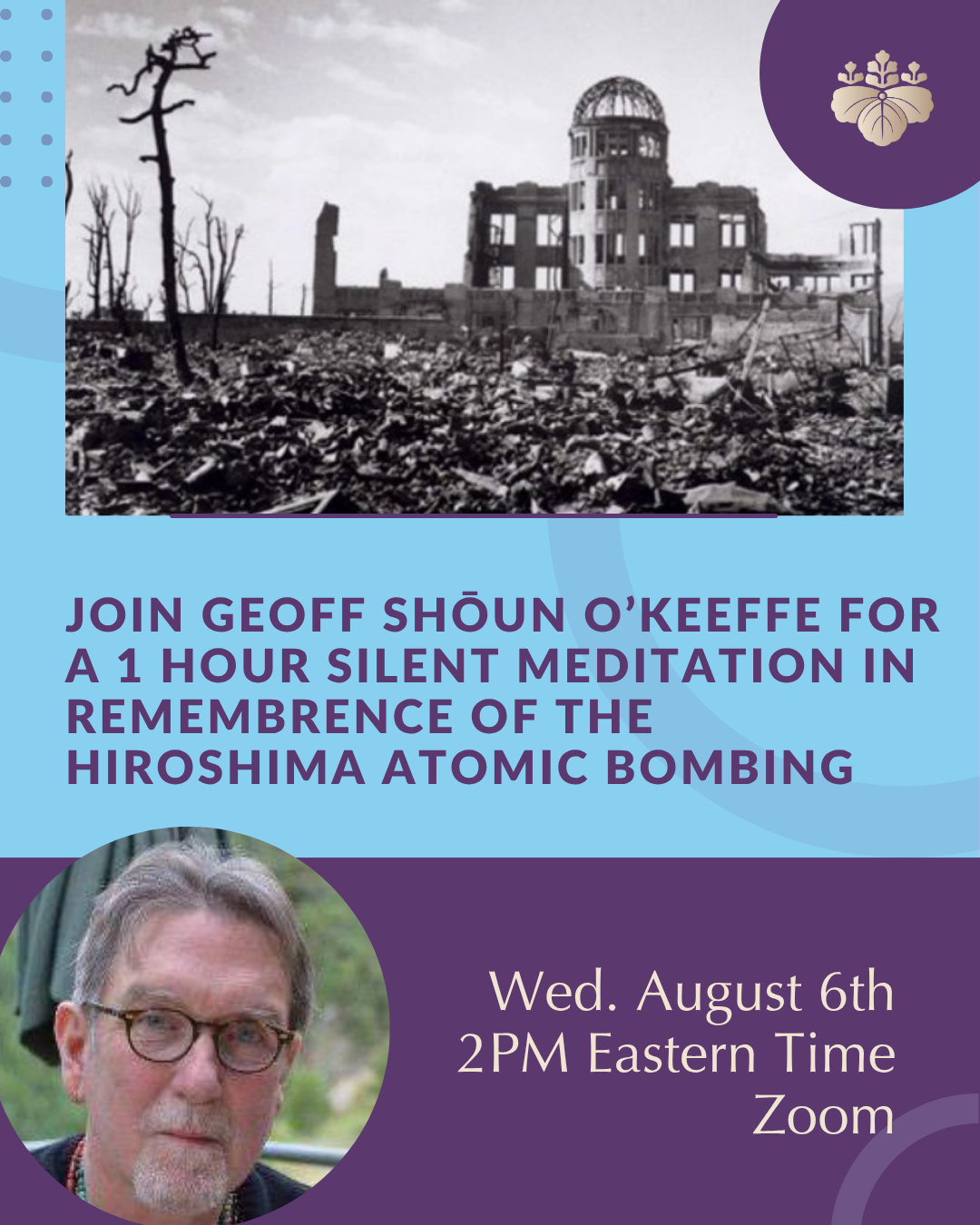

At the Zen Peacemakers, which my former wife, Sandra Jishu Holmes, and I co-founded, we practice three Core Tenets: Penetrating the unknown by letting go of our fixed ideas; bearing witness to joy and suffering, and loving actions. At Auschwitz, it is not hard to let go of fixed ideas. The place itself, with its endless gray skies overlooking miles of barbed wire and crumbling extermination compounds, is so terrifying that no matter how much we prepare for the visit, no matter how much we’ve read about it or pondered, it overwhelms us. Even if, like me, you’ve seen the exhibits more than once and have even walked several times down the endless railroad tracks that once brought so many to their end, there’s one thing you can still count on: Your expectations, your preconceptions, your most basic belief systems concerning love and hate, good and evil, will be annihilated in the face of Auschwitz.

In fact, after seeing the endless photographs of dying camp inmates and the high piles of their belongings pillaged by the Nazis, and after visiting Birkenau and viewing the remains of that meticulous technology developed for the purpose of mass extermination and genocide, we stop thinking altogether. As writers and philosophers have already said, there’s no language for Auschwitz. I can only add, there are no thoughts, either. We are in a place of unknowing. Much of Zen practice, including many teaching techniques used by Zen masters, is aimed at bringing the Zen practitioner to this same place of unknowing, of letting go of what he or she knows.

After walking through Auschwitz and Birkenau, there is an end to thought. We are numbed. All we can do is see the endless train tracks on the snow, feel the icy cold of a Polish winter on our bare hands, smell the rotting wood in the few remaining barracks, and listen to the names of the dead. At Birkenau we don’t sit in silence, we chant names. First, we sit in a large circle around the railroad tracks, at what was once the Selection Site, directly opposite the crematoriums. A shofar blows to start the meditation period, and then four different people, each sitting at a different point on the rim of the circle, begin to chant the names of those who’d died at Auschwitz. The names come from official lists compiled by the SS. They’re also provided to us by various retreat participants, obtained from memory, family, and friends. All of us take turns chanting names. Elisa Sara Fein (10.3.1907-8.12.1943)Heinrich Israel Feiner (8.3.1878-2.1.1944) Markus Fejer (14.7.1925-19.6.1942) Rywa Sara Feld (5.12.1911-6.12.194)). We chant for ten minutes, and then the person sitting next to us begins. The lists include the victims’ dates of birth and death. That’s how we know that some were very old, and some were only infants. But we don’t chant the dates, only the names. Lilly Ernst (9.2.1939-17.1.1944) Hugo Fenyvesi (27.10.1875-5.5.1942) Sophie Ferko (15.3.1943-21.5.1944).

We are a global group, so the names are chanted by American, Irish, Dutch, Italian, German, Swiss, Israeli, Polish, and French voices. The names themselves are also from a multitude of languages. Everyone gets their turn. Across the large circle, we hear the names. Sometimes one resembles the name of a co-worker back home, or of a friend. Sometimes the chanter pauses. She’s come across a name that’s exactly like her own. For telling names is like telling stories. When we recite the name out loud, dead bones come to life, the bones of men, women, and children from all over Europe. They lived, some grew up, some married, some had children, and all died. Their names become our names, their stories, our stories. That is what happens when we bear witness.

Peter Grosz, an American living in the Czech Republic who participated in a retreat, recently wrote us (many of the people who attend send us letters, articles, and journal entries describing their experiences). Discussing the meaning of bearing witness, he wrote the following: “You can have seen what you’ve seen and never be a witness. You can see the whole world and never have witnessed anything. Only when what you see becomes significant to someone — to yourself, for instance — do you become a witness.” How does something become significant? What is this process of witnessing, or bearing witness, that is more than just seeing? When we bear witness to a situation, we become each and every aspect of that situation. When we bear witness to Auschwitz, at that moment there is no separation between us and the people who died. There is also no separation between us and the people who killed. We ourselves, as individuals, with our identities and ego structure, disappear, and we become the terrified people getting off the trains, the indifferent or brutal guards, the snarling dogs, the doctor who points right or left, the smoke and ash belching from the chimneys. When we bear witness to Auschwitz, we are nothing but all the elements of Auschwitz. It is not an act of will, it is an act of letting go. What we let go of is the concept of the person we think we are. It’s why we start from unknowing. Only then can we become all the voices of the universe — those that suffer, those that inflict suffering, and those that stand idly by. For we are all these people. We are the universe.

After five days of sitting at the Selection Site and chanting names, many could see themselves as those who had gone to the gas chambers, including those who had no direct family connection to Auschwitz. Mothers thought of themselves bringing their own children into the death chambers. Men saw their own bodies going up in smoke in the crematoria. It was harder to see oneself as a guard who’d herded people to their death. One of the retreat participants was a Vietnam veteran. He said that he could see himself as one of the guards on top of the guardposts, aiming his gun at the people below. But not many people could see themselves that way. The famous prayer about oneness, the Sh’ma Yisrael, begins with Listen: Listen, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One. Not only does oneness begin with listening, but listening also begins with oneness. And Zen Peacemaker Order’s Buddhist service begins similarly: Attention! Attention! Raising the Mind of Compassion, the Supreme Meal is offered to all the hungry spirits throughout space and time, filling the smallest particle to the largest space. Listen! Attention! Bear witness!

It can’t happen if you want to stay away from pain and suffering. It probably won’t happen if, like most people, you go to Auschwitz, look over the exhibits, and return to the buses for a quick getaway. When you come to Auschwitz, stay a while, and begin to listen to all the voices of that terrible universe — the voices that are none other than you — then something happens. During a retreat, a man of Jewish descent living in Denmark stood up one evening and spoke about forgiving those who had perpetrated cruelties at Auschwitz. A short while later I stood up and suggested: “And then what? So you forgive, and then what? Is that the end of it? Or is there something else to be done?” If I really bear witness, if I become all the voices of Auschwitz, then it is myself that I am forgiving, no one else. If I see that at every moment a part of me is raping, while another is being raped. A part of me is destroying while another part is being destroyed. A part of me goes hungry while another eats to excess. A part of me is paralyzed and a part of me takes action. Then it makes no sense to stay in the place of blame and guilt, of anger and accusation. When I begin to see that all these parts are me, I can begin to take care of the situation.

When we’re bearing witness to Auschwitz, we’re doing nothing other than bearing witness to aspects of ourselves. It’s no different when we bear witness to poverty, homelessness, hunger, and disease. We see how one part of us does something, and another part of us suffers. If we get stuck in anger and in guilt, then we’re paralyzed, we can’t act. Only when we see that all these demons are nothing other than us, we can actually take action. Then we can begin to take care of the other, who is none other than our self. In Buddhism, we say that we are all constantly transmigrating from one realm to another at every minute. There are the hell realm and the realm of the gods. There is also a realm of hungry ghosts. One of our images for a hungry ghost is a painfully thin person with a tiny mouth, a long, narrow throat, and an immense stomach. The hungry ghost is always hungry but has only a tiny capacity to absorb the nourishment that he needs.

I go back to Auschwitz again and again for this reason: Each time I return to that huge death camp I realize anew that I am full of hungry ghosts. I’m full of clinging, craving, unsatisfied spirits. Each part of me that is struggling, in pain, unsatisfied, angry, and unresolved, is a hungry ghost. A starving child, an abusive parent, a stricken mother leading her child into the death chamber, a brutal guard, a drug addict who kills to get his fix, they are all starving, struggling aspects of me. Me is everyone and everything, including those that look away. At the end of his long letter to me, Peter added: “Auschwitz is a Godless place only for those who see it as bereft of voice.” He stayed there for five days and found Auschwitz full of voices, all of them his own. Attention! Attention! Raising the Mind of Compassion, the Supreme Meal is offered to all the hungry spirits throughout space and time, filling the smallest particle to the largest space. All you hungry spirits in the Ten Directions, please gather here. Sharing your distress, I offer you this food, hoping it will resolve your thirsts and hungers.

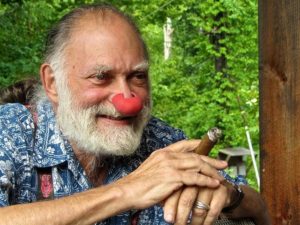

About the Author:

Zen Master Bernie Glassman, the founder of Zen Peacemakers, was a world-renowned pioneer in the American Zen Movement. He was a spiritual leader, published author, accomplished academic and successful businessman. Bernie spent decades teaching Zen and working in Socially Engaged Buddhism, founding Zen Peacemakers in 1996 and developing Bearing Witness Retreats. He passed away in Massachusetts USA on November 4th, 2018 from natural causes. It was the eve of the 23rd Zen Peacemakers Auschwitz-Birkenau Bearing Witness Retreat

Zen Master Bernie Glassman, the founder of Zen Peacemakers, was a world-renowned pioneer in the American Zen Movement. He was a spiritual leader, published author, accomplished academic and successful businessman. Bernie spent decades teaching Zen and working in Socially Engaged Buddhism, founding Zen Peacemakers in 1996 and developing Bearing Witness Retreats. He passed away in Massachusetts USA on November 4th, 2018 from natural causes. It was the eve of the 23rd Zen Peacemakers Auschwitz-Birkenau Bearing Witness Retreat