Another World is Possible

Transformation through Hospitality and Dialogue in the Syrian Desert

About an hour north of Damascus, carved into a rocky ridge in the Syrian desert, sits a monastery called Deir Mar Musa. Originally built in the 11th century, it’s the kind of place that breathes with history. Frescoes, now faded and cracking, still glow faintly across the chapel walls—scenes of saints and apostles and the life of Christ. Behind the main building, stone crosses mark caves where hermits once prayed in solitude, choosing silence and simplicity in this harsh, beautiful wilderness.

The monastery was abandoned for a time, until the 1980s when a Jesuit monk named Paolo Dall’Oglio arrived on pilgrimage. He found the place in ruins—but saw, somehow, its soul still intact. He stayed, and others came. Together they rebuilt Deir Mar Musa not just as a place of prayer and labor, but as a living witness to hospitality and interfaith dialogue. People from around the world arrived—Christians, Muslims, seekers, skeptics—and they were all received the same way. With joy. With a cup of tea. With the question, “What language do you speak?”

That question was the beginning of belonging. Not what you believed. Not where you were from. Just: how can we meet you where you are?

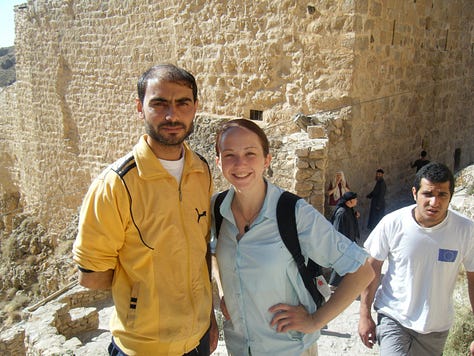

I know this because I was one of those travelers. In the summer of 2010, I climbed the 350-plus stairs etched into the mountainside, hot and dusty and unsure of what I would find. I came as part of my work in interfaith dialogue and the completion of my master’s degree. But what I found wasn’t academic. It was embodied. I came to learn about hospitality and dialogue; instead, I was received into it.

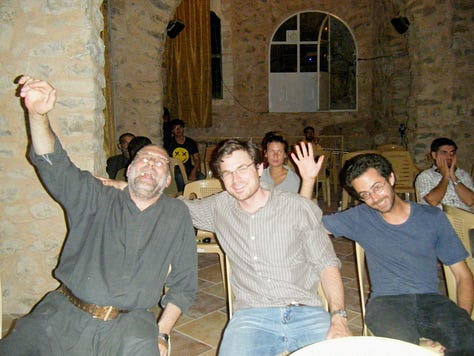

The focus of community life at Deir Mar Musa is work, prayer, hospitality, and dialogue. Everything at Deir Mar Musa revolves around the rhythms of building community life together: prayer services, meals, shared work, shared silence. We carried stones, chopped vegetables, organized the little shop Br. Youssef was trying to reopen. We prayed together. We drank tea. We played with kittens. We laughed in ten languages and often didn’t understand a word—and somehow it didn’t matter.

It was in that space between languages that something deeper emerged. We had to really see each other. We had to ask questions and wait for slow answers, often in gestures or laughter or guesses. It required patience. It required humility. But more than that, it required love. A simple, openhearted willingness to behold the person in front of you as beloved.

That’s what transformed me.

I felt it most powerfully during community prayer. Before entering the chapel, we removed our shoes, as in a mosque. We stepped onto layers of rugs, sitting side-by-side on the floor, and sat on cushions. The design of the chapel facilitated Muslim belonging in a space they are traditionally othered. The Mass was primarily in Arabic—sometimes with pieces in French or Latin or English. But when the Lord’s Prayer was said, we all spoke in our own languages, layered voices echoing off the stone walls, rising like incense.

I didn’t understand most of the words. I didn’t need to. I belonged.

While I cannot comprehend, on one level, a service in Arabic, my heart opened in prayer. As an outsider to the Catholic faith, an outsider in Syria, an outsider to the Arabic language… I still absolutely belonged. To pray with Catholics, Muslims, Druze, seekers, agnostics… openly, authentically, genuinely, made belonging palpable for all of us.

I remember one night sitting beside a Muslim woman from London. We greeted each other quietly before the service, and then we sat, praying together. Afterward, over dinner, we were joined by a Catholic couple from Poland. The conversation that unfolded felt like holy ground: each of us confessing our nervousness before the service, and then each of us admitting how safe and whole and welcome we’d felt. The Muslim woman said she had never felt so at home in a church. The design and language grounded her with God. The Catholic couple said it was one of the deepest spiritual experiences of their lives. Although they did not speak Arabic the flow of the familiar liturgy habitually drew them into prayer. I just nodded, my heart too full for words.

There was a night when two young Danish women returned to the monastery carrying fruit, nuts, and heavy cream. They wanted to make a fruit pudding from home. We all took turns in the prep kitchen, trying to whip cream into stiff peaks by hand, passing around wooden spoons and giggling and the ridiculousness of hand whipping whipped cream. We told stories about pudding desserts from Russia, China, Somalia, Syria, Belgium, Canada, the U.S.—and in all of it, we held one another in a joy that didn’t need translation. Muslims, Christians, agnostics, monks, travelers, pilgrims—all just people, helping each other stir something into being.

We made fruit pudding, yes. But really, we were building community.

I think about that monastery often. My heart aches for it, still. For the sacred hush of prayer in Arabic, for the desert sun setting on the sandstone walls, for the laughter around a shared table. For the way I belonged—not because I said the right words or believed the right things, but because I showed up. Because I was part of the community – even for a month.

And what I carry now is the knowing that this kind of belonging isn’t just a dream or a utopia. It’s possible. It’s real. I’ve touched it with my hands. Sat in it. Prayed in it. Eaten fruit pudding in it.

Deir Mar Musa taught me that hospitality isn’t about perfect hosting or grand gestures. It’s about presence. Curiosity. Reverence for the story someone carries. Dialogue isn’t always formal—it’s the choice to be open-hearted with the person right in front of you. To ask, “What language do you speak?” and wait long enough to understand what they’re really saying.

And it helps to offer a cup of tea.

There is much more to this adventure, travels up to Aleppo and staying with a family who welcomed us (Caitlin and me) into their house while we traveled; many people, much prayer, and profound joy. I offer this piece of the story as a glimpse of the world that is possible if fearless, open-hearted hospitality is taken seriously.