I was in Takoma Park, Maryland, for the Thanksgiving holiday and returned home on Saturday. The following morning, I took out the dogs in freezing temperatures on one of our favorite walks, Fiske Pond in the Town of Wendell, some 10 minutes from the house.

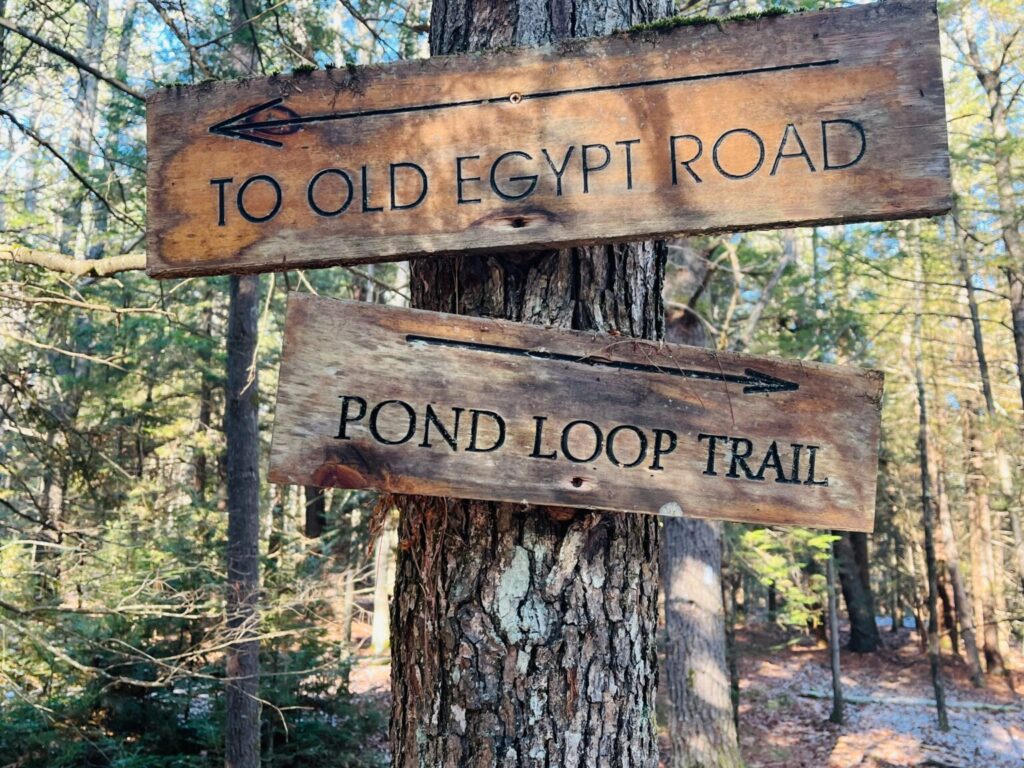

The place had changed dramatically in just a week. Beavers have been busy, the water table rose, and we had a hard time crossing over pools that a week ago were perfectly accessible. So we walked the other way down snow-strewn paths and across slippery rocks till I came to a familiar signpost.

The Pond Loop Trail, which we usually pursue, goes around Fiske Pond, only this time we couldn’t follow it completely. And then there’s the alternative: Old Egypt Road.

For Biblical Jews, Egypt symbolizes the place of enslavement, where so many thousands labored to build the great tombs and pyramids for the Pharaohs. It was the place you left if you wanted freedom: Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt land. Tell old Pharoah: Let my people go.

This time it hit me that Old Egypt Road marks the path of the bodhisattva, the life path of the true human being, the mensch, as Bernie liked to call it. Bodhisattva literally means an enlightened being, or someone on the path to enlightenment. But, as the Founder of Soto Zen had written, that person vows to not cross the bridge towards full awakening till all beings have crossed first. Hers is not a path towards bliss but rather taking her place among all suffering beings and helping, always helping.

She takes the trail back to Old Egypt, where people are enslaved not just by social and hierarchical structures, and not just due to their ethnic or religious origins, but also due to the separation they swear by, their alienation from the rest of the world, listening to mind chatter about past regrets and future fears, sitting on judgment of people and life rather than fully embracing, fully living.

Instead of trekking to the Promised Land, she goes back to Old Egypt to put her training into use and her practice into service of others. And indeed, the dogs and I turned right rather than left and went up that trail for a long time.

Richard Powers, author of The Overstory, wrote this in his new book, Playground: A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.

In the bodhisattva’s game, there is no winning. It’s an infinite game and you’ve vowed to play it forever. Playing it becomes the most important thing in your life regardless of who wins and who loses.

Every month two immigrant sisters give our house a thorough cleaning. The one who speaks good English, Marta (not her real name), has been here for at least 20 years, but is still undocumented. I have no idea if she has filed papers seeking asylum or not, I just know that she left behind a child, a young daughter, and hasn’t seen her in over two decades.

It’s painful for Marta when we broach the topic, so I don’t ask her about the circumstances. She can’t go back to see her now grown-up daughter because she won’t be allowed back here, where she has a husband and another, younger daughter. She and her sister think nothing of cleaning 3 and even 4 homes a day, though neither is especially young.

“Why do you work that hard?” I ask her.

“I want to buy a home for my daughter,” she says. “The daughter back there.”

Old Egypt is in those eyes. She came on that arduous, dangerous journey up here to clean homes for decades so that she could buy a home for the daughter she left behind.

But you can find happiness everywhere, even in Old Egypt. Yesterday, Marta arrived alone.

“Where is your sister?”

“I didn’t work this morning. Instead, I took my driver’s test and after that I came here.”

“And?”

Her eyes lit up like the sun. “I passed! I can drive now!”

In a referendum last year, Massachusetts voters overwhelmingly voted to let all immigrants—legal and illegal—obtain a driver’s license. Another one of Jimena Pareja’s multiple jobs is to help them get a Learners Permit, which necessitates some English.

We hugged ecstatically. I have never seen her so happy. She laughed and almost cried; she was so proud of herself. I remembered my own joy at getting my driver’s license at the age of 18, what confidence it gave me, a sense that now I could really do things on my own. This woman is somewhere in her mid to late 40s and no longer has to rely on her husband to drive her, she can get behind the wheel and go the distance. We were two women joined in joy of freedom and independence.

“Your first test?”

“Yes, my first test!” Another hug. We felt like dancing around the table.

That, too, is part of Old Egypt Road.

It’s the game you play forever, like the old marriage vows: for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health. To love and to cherish.

Eve Marko is a Founding Teacher of the Zen Peacemaker Order and head teacher at the Green River Zen Center in Massachusetts. She received Dharma Transmission and inka from Bernie Glassman. She is also a writer and editor of fiction and nonfiction.

Eve has trained spiritually-based social activists and peacemakers in the US, Europe, and the Middle East, and has been a Spiritholder at retreats bearing witness to genocide at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Rwanda, and the Black Hills in South Dakota. Before that, she worked at the Greyston Mandala, which provides housing, child care, jobs, and AIDS-related medical services in Yonkers, New York.

Eve’s articles on social activists have appeared in the magazines Tricycle, Shambhala Sun, and Tikkun. Her collection of Zen koans for modern Zen practitioners in collaboration with Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao, The Book of Householder Koans: Waking Up In the Land of Attachments, came out in February 2020.

Hunt for the Lynx, the first in her fantasy trilogy, The Dogs of the Kiskadee Hills, was published in 2016.

“When I was a young girl my dream was to be a hermit, live alone, and write serious literature. That’s not how things turned out. I got involved with people. I got involved in the world. Two things matter to me right now: the creative spark and the aliveness of personal connection. In some way, they both come down to the same thing.”